Remember that scene from Mary Poppins where Burt, Mary and the children are standing with their toes on the edge of Burt’s chalk drawings, about to jump in? It was the height of imagination in film, and it has been the dream of every child ever since: to have the ability to step from reality into a picture. Imagine having that ability with your own photographs; to turn a two dimensional rendering into a tangible experience. How? Let’s start with the landscape photograph.

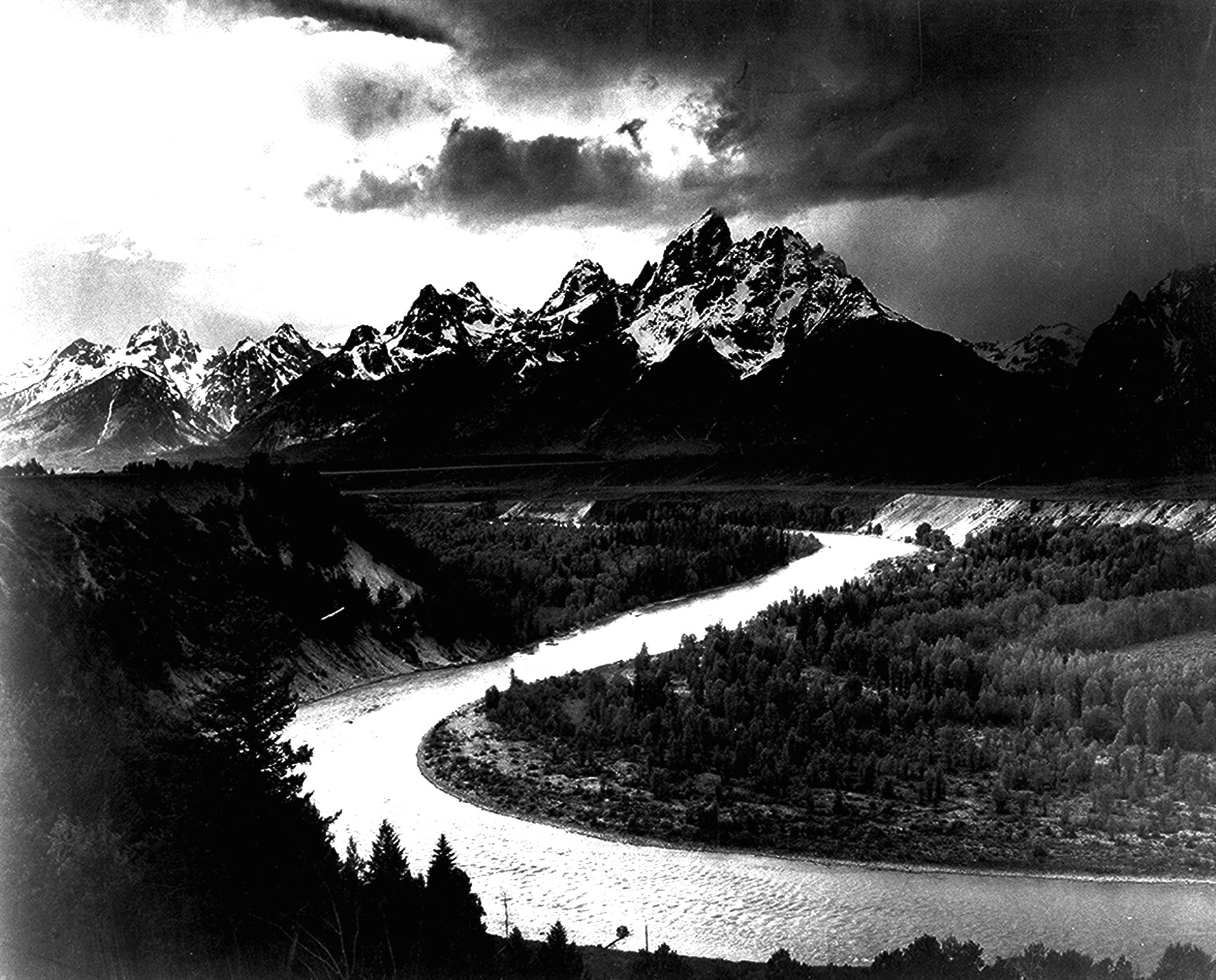

The beauty of landscape photography lies in what is missing: the absence of human activity. No facial expressions or moving limbs to draw the focus away from the surroundings. It is all about the wide stretches of land, unsullied and unspoiled by human productivity. The textures and depth are drawn from the defined landmasses, ambient light, and whatever details are put there by nature. Master photographers Edward Weston and Ansel Adams were renowned for their ability to capture the various forms of the American landscape. Their works became the standard by which future landscape photographers would be judged.

Many novice photographers make the mistake of thinking that ‘landscape’ equals ‘rural.’ City dwellers rejoice! The definition of “landscape photography” has grown to encompass industrial areas and urban skylines. Although most landscape photography is based on the traditional guidelines set down by the American masters, a revolution has been taking place, narrowing the gap between ‘rural landscape photography’ and ‘urban landscape photography.’ Noted landscape photographers, like Smithsonian Fellow Barbara Southworth, have turned their lenses from the southern wetlands to the high-rises of New York.

So how does lenticular 3D printing fit in to building a better landscape photograph? It is all about presentation and depth. The portfolio of contemporary landscape photographer David Winston is a prime example of how to craft 3D lenticular landscapes.

There are a number of different techniques available to help you take your landscape to the next level. Start by choosing a setting with multiple planes, with a single object for focus. The Stereoscopic method is the most reliable way to create the illusion of 3D; this involves capturing a minimum of two images of the same object, but at different angles. This can be achieved by using two cameras, set apart by about 65mm to copy the distance between the human eyes.

Another technique is to use one camera on a rolling platform moved quickly between two positions. Back in the early to mid-20th century, stereo cameras were popular; each camera had a series of two or more lenses to capture the subject from different perspectives.

Every photographer has his or her own preferred technique. You should find the method that fits your style and hone it. Then seek out a subject; when working in landscape photography, I suggest you start with a place that is familiar to you and has enough space for you to experiment until you find the sweet spot. After that, it is all practice, practice, practice!

![]() Beth Garland is a 32 year old photographer and writer. The Nebraska native picked up her first Canon AE-1 at age 14 and has been snapping away ever since. A fervent devotee of National Geographic, she takes every opportunity she can to travel. Since wending her way around the world, she has upgraded to a Canon PowerShot, but anticipates buying a high end digital SLR. In the meantime, she experiments with printing techniques, blogging and having a good time!

Beth Garland is a 32 year old photographer and writer. The Nebraska native picked up her first Canon AE-1 at age 14 and has been snapping away ever since. A fervent devotee of National Geographic, she takes every opportunity she can to travel. Since wending her way around the world, she has upgraded to a Canon PowerShot, but anticipates buying a high end digital SLR. In the meantime, she experiments with printing techniques, blogging and having a good time!